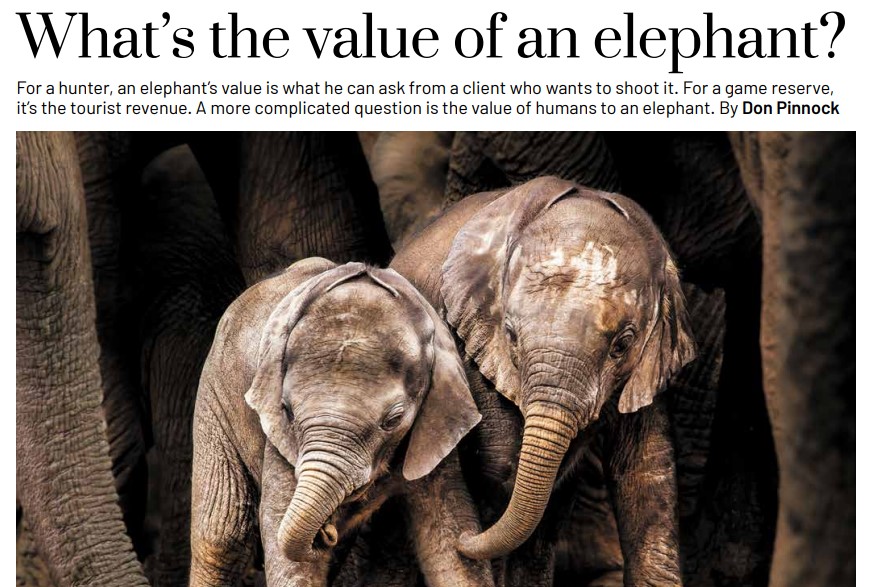

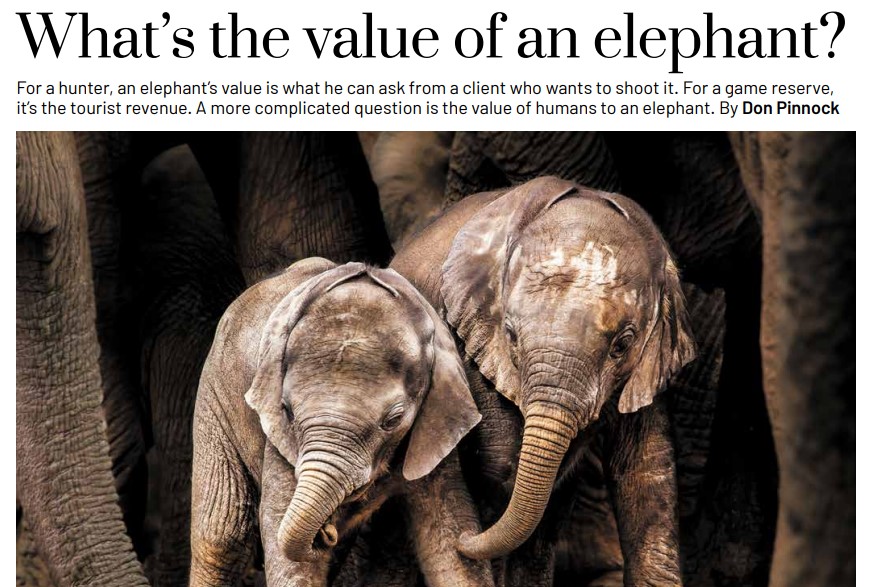

For a hunter, an elephant’s value is what he can ask from a client who wants to shoot it. For a game reserve, it’s the tourist revenue. A more complicated question is the value of humans to an elephant. By Don Pinnock, Daily Maverick, 11-17 Feb 2023.

In a time of increasing pressure on the natural world, valuing a single creature like an elephant is critical to its conservation – but damnably difficult. We generally think of value in terms of money, but that’s a very narrow definition. Value implies benefit. So who and what benefits from an elephant apart from actually being an elephant? And why is it important to know this?

Here’s why. We have become so used to using the raw materials and creatures of the natural world for our benefit that it’s difficult to think in any other way. It’s what ensured our survival and eventual domination. But this has come at a cost, especially to wild creatures. Of all the mammals on the planet, including us, wild mammals constitute a mere 4%. If we want what’s left to survive, we have to value them for more than their use to ourselves. Elephants are a good starting point. They’re a keystone species whose numbers have plummeted dramatically over the past 100 years because of us. Valuing them beyond their use to us is essential for their survival.

This is what four researchers, Antoinette van de Water, Michelle Henley, Lucy Bates and Rob Slotow – all with huge experience in the field – set about trying to do. Their starting point and first problem was the marketplace. Read the article “What’s the value of an elephant?”

There is a tendency, they say, for us to view the relationship between nature and people as a one-way flow from nature to people, with nature providing the goods and opportunities without reciprocity. This is highly anthropocentric and often colours policy decisions about elephant conservation.

Most modern people (but not indigenous groups) value things in terms of their monetary cost in an economy that links value to growth. But when economic benefits alone are acknowledged, say the researchers, the danger is that all non-economic benefits and values will be overlooked.

This is a big problem in making policy on conservation or planning systems that deal with wildlife. There’s an inbuilt, almost unconscious, bias towards human use, which means we overlook the fact that they are useful in many other ways to other creatures and systems.

For elephants, these “other” values include habitat engineering, influencing tree/grass coexistence and biodiversity, improving soil nutrients and providing microhabitats for creatures like dung beetles. To us, they also have value far greater than a trophy above the fireplace, such as our sense of wellbeing and awe in coming across elephants in their natural habitat, and as a sacred dimension for indigenous people.

Monetising elephants by selling them or poaching them for ivory is easy to understand – it’s all about being a product for sale. They’re a value to people who do that and no value whatsoever to elephants. But if you’re a conservationist seeking their protection, you’re up against trade-offs between funders, legislators, hunters and a subsistence farmer who just had his crop trashed.

Whose values should prevail? The researchers focused on the nature and implications of such trade-offs in decision making.

A routine trade-off is one between two conflicting secular values. An example would be between allowing ivory sales to satisfy demand and possibly reduce poaching against the argument that permitting ivory trade will increase demand in destination countries and so increase poaching.

Tragic trade-offs are when decisions involve two conflicting sacred values, where one needs to be sacrificed to enable the other – always emotionally difficult and stressful. This could involve proposals to evict indigenous people from their land or prohibit cattle grazing to reduce threats from elephants and protect fragile grassland set against moral arguments related to human rights.

Taboo trade-offs occur when secular principles are at variance with sacred or traditional principles. An example could be using trophy hunting to support community development set against moral arguments based on the intrinsic value of an elephant’s life.

Other examples are proposals to financially compensate for the loss of life as a solution to human-elephant conflict countered by the morality of putting a price tag on human life, or exploiting elephants for entertainment to fund local conservation or development, as against the cruelty of training them.

Another such trade-off could be culling elephants to reduce environmental pressure countered by protests motivated by the intrinsic value of elephants and their rights.

Marginalising trade-offs occur when culturally sacred principles are overruled by secular principles.

The losers tend to be a minority or disempowered group, leading to the perception that their principles are insignificant or peripheral.

The researchers warn that promoting the belief that nature stays if it pays will lead to decisions based only on instrumental benefits. Although the ivory trade, poaching, culling and trophy hunting may provide shortterm gains, they encourage unsustainable natural resource extraction without calculating the cost of long-term conservation.

Killing an elephant that caused damage or a large-tusked trophy bull could compromise many other ecological, relational and moral values. It could undermine long-term viability of the herd and existence value.

Internationally, elephants are rated by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in terms of our threat to their existence. Two species, African and Asian, are classified as endangered and African forest elephants as critically endangered. But, at local or regional levels, their conservation status may differ.

In South Africa, the regional Red List status of the savanna elephant is defined as of “least concern” and the elephant populations are listed as Appendix II in Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe and Appendix I elsewhere.

A further complication arises as elephants are highly migratory; their national status changes as they move across country boundaries. When they travel through communities they overlap with people who value them differently – from pro-hunting to sacred. Other issues arise with such migrations. Proposals to allow elephants to roam freely based on rights of passage and increasing connectivity can conflict with the issue of so-called damage-causing-animal permits to shoot roaming elephants.

Proposals to ban ivory trade or commercial exploitation of elephants based on intrinsic value and rights is countered by the need for economic development and conservation funding. Compared to routine and tragic trade-offs, the researchers found, taboo and marginalising ones are much more challenging, psychologically uncomfortable, emotion-laden and often repugnant. Though they may be scientifically or politically viable, they can lead to moral outrage or social unrest.

In broadening the notion of elephant value, the researchers found a startling 87 benefits accrued from them beyond conventional uses like hunting, poaching and tourism. These include being key to habitat biodiversity, habitat engineering, increasing food availability for browsers by pulling down trees, topsoil and forest litter formation, ecotourism, job creation, increasing land value, branding and marketing, artistic worth, promotion benefits, human therapeutic and wellbeing benefits, compassion, wildlife research, indigenous wisdom, symbolism, folklore and national heritage.

Such categorisation allows policymakers to avoid a flawed, one-way value chain when they face the kinds of problems that arise and trade-offs that must be dealt with in elephant conservation. This thinking can also be applied by local managers developing park management plans or intervention projects who may not have time or capacity to understand all the values at stake. To this end, the researchers developed a visual checklist tool against which decisions can be made.

The vast research on elephants, they say, enabled them to develop this comprehensive overview, which may not have been possible for other less well-studied species or ecosystems, but can now be applied to other species and ecosystems. And the value of humans to an elephant? Without a doubt it’s when we’re not anywhere near them and stay there. DM168

‹ Back to previous page